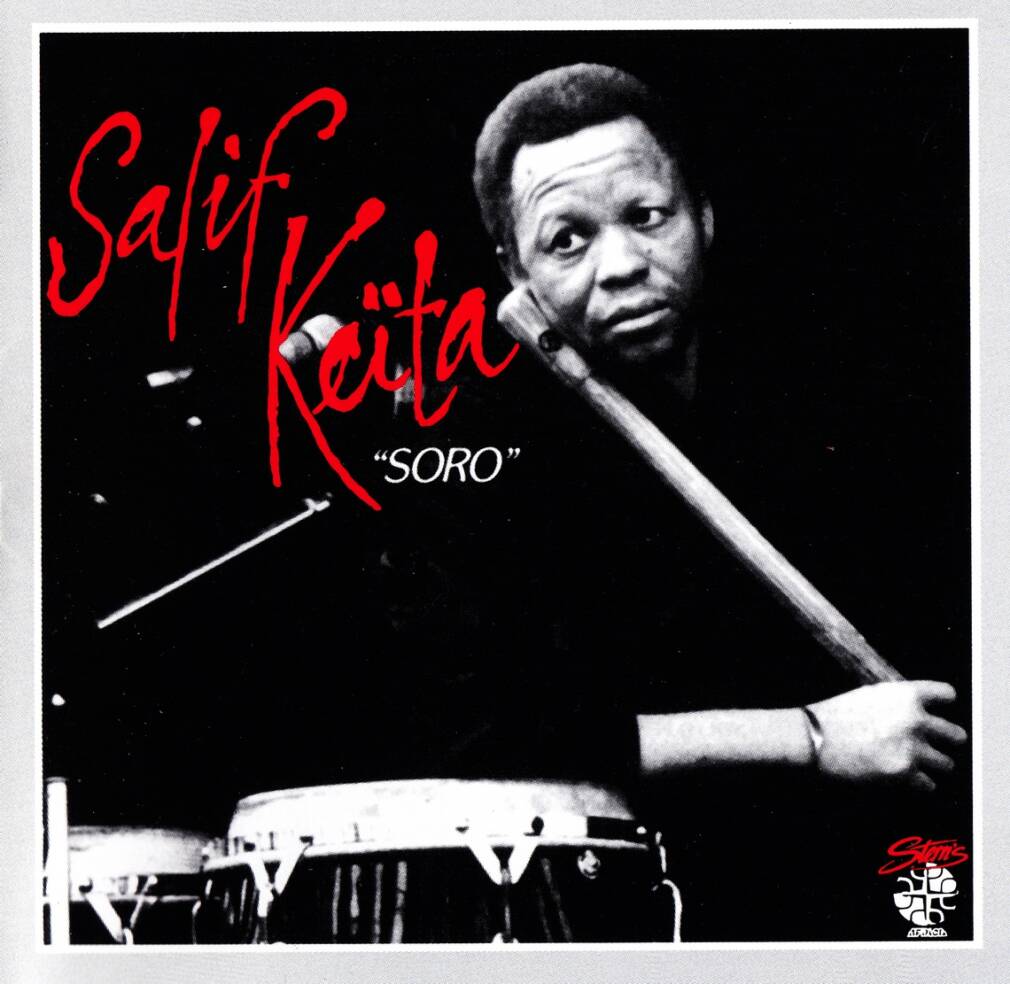

Salif Keita’s Soro released in 1987 and recorded at Studio Harry Son in Paris stands as a time capsule of a particularly creative milieu and arguably an early work of afro-futurism. A cornerstone of Keita’s cannon and indeed the careers of all involved – This defining album of the eighties was executive produced by Ibrahima Sylla alongside François Bréant and featured a pan-African personnel present in Paris at the time, as well as genie of the synth Jean-Philippe Rykiel.

A record that can sit comfortably alongside Immigrés by Youssou N’dour (1988) and Le Voyageur by Papa Wemba (1992), it baffled more reductive ears who for Bréant expect African music to be “a museum” and “a bone through the nose and bells on the feet” listeners eager to be served the same dish again and desiring of a record to neatly file in a carefully curated collection.

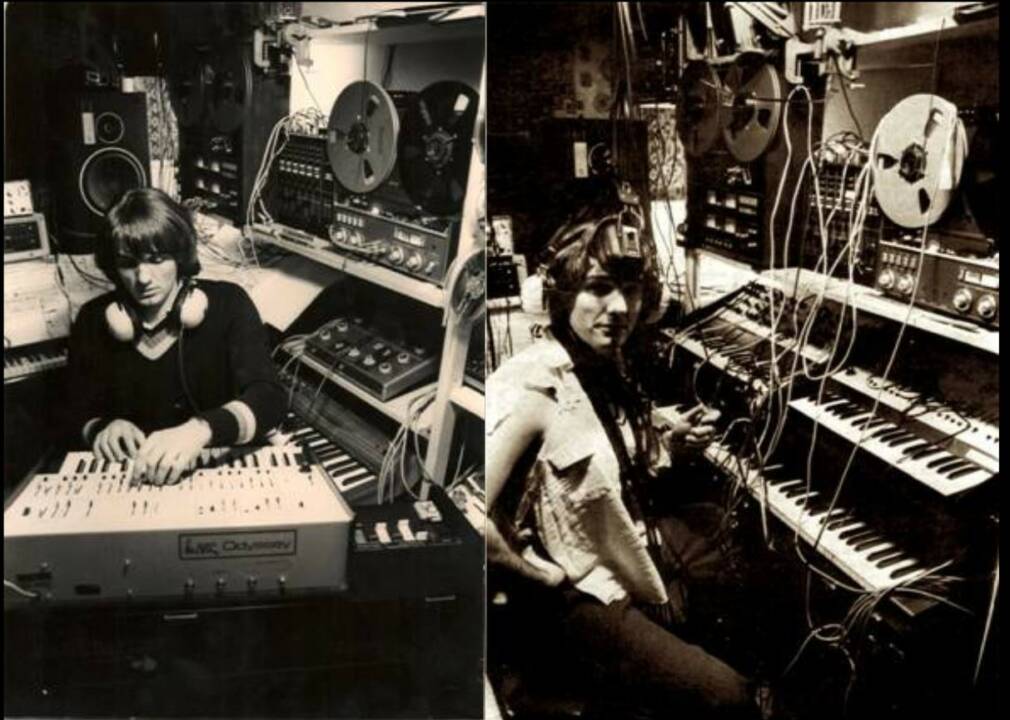

Instead, Soro sought to say something new with what the liner notes of Nii Yamotei described as “state of the art technology” by using synths and production to do justice to the perfection of Salif’s craft.

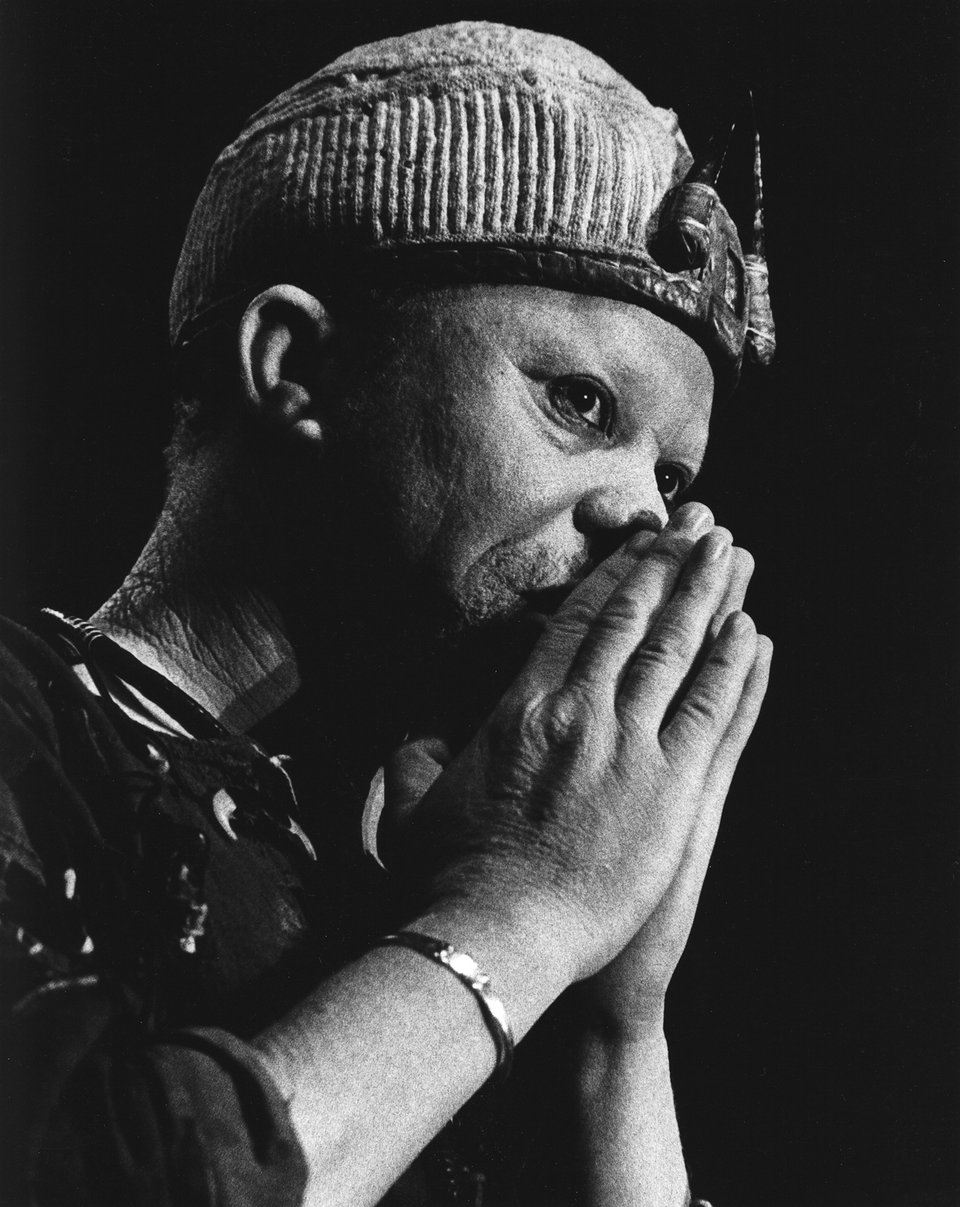

Resident in Paris since 1984, Salif Keita was already a star in West Africa at the time work began on Soro. Having honed his voice first with the Super Rail Band De Bamako and later with Les Ambassadeurs, this direct descendent of Sundiata Keita (the founder of the pre-colonial empire of Mali) had overcome prejudice and conservatism in his path to professionalism. Shunned as a person with albinism, and forbidden to sing as a result of his noble birth, Keita could cite a variety of reasons to relocate to Paris.

The hub for musicians of the African diaspora in Paris at this time was a small record shop situated near the Gare du Nord. Kubaney Music run by Ibrahima Sylla on Rue de Rocroy was both a meeting place and laboratory for creativity, and could be compared to Sterns Record Shop in London during the same epoch.Son of a diplomat and an erstwhile economics student – Sylla had founded the Syllart label in Dakar in 1978, producing records for Orchestra Baobab and licensing and releasing cassette recordings made by African artists between the sixties and eighties.

Completing the team that would converge on Studio Harry Son came conjurer of the keyboard Jean-Philippe Rykiel, and producer François Bréant, who confesses to a certain stage fright when Salif first visited to start preparations for the album:

“I remember when Salif came to my home studio for us to prepare. Very often African musicians arrive with a court of friends and when Salif came it was fifteen people in total in my studio there to give Salif their opinion on whether he could trust me.”

With Salif satisfied, work began with Bréant asking for a tempo for each song and setting up a click with the desired beats per minute, alongside a drone for each song to provide a tonal reference. Over this Salif sung ideas whilst picking out some arpeggios on his acoustic guitar and in this way several of the tracks were built up with François immediately struck by the commitment with which Salif approached any vocal:

“Something that impressed me with Salif was that whether it’s a demo, or mic test or whatever, he sang like it was the last time of his life, and the emotion, expression and artistic content is there all the time. I thought he’s not faking! He’s not restraining, he was doing it whether it was important or not.”

This mastery is evident from the first seconds of Soro as the album takes off with “Wamba” on which Salif cries out with all a griot’s vibrato and melisma (despite not being from the artisanal cast) and is answered by a female choir in perfectly matched counterpoint. Indeed, Soro shows us what it’s about immediately as Cameroonian drummer Brice Wassy locks in with bassist Michel Alibo and guitarist Yves Ndjock trades with Rykiel’s synths.

With engineer Hervé Marignac at the desk and the best players in Paris being called for the sessions, work was under way with Bréant clear on what his role would be:

“It was for me to restrain my influence. I wasn’t there to give them music lessons! I never forget that I’m a white man from France and I’ve seen many collaborations slide into disco records with African flavours as added exoticism.”

As musicians like Cheikh Tidiane Seck reported for work François realised that Soro would be a special record thanks to: “A reservoir of African musicians in Paris coming from all over Africa and a blend from France, Cameroon, Martinique and Mali.”

This pan-Africanism allowed the team to depart from any traditional matrix for folkloric music and notions of what was allowed or acceptable:

“Since I was naive about music especially at this time” Bréant begins “I could say: “It would be nice to add a Peul flute here.” And Salf might say: “But I’m not Peul! are you sure?” But they forgave my naivety and I was permitted to offer ideas they might have thought were bizarre if I was a Malinké producer”

That said, Bréant remembers making a proposition for a bass line in “Squareba” and executive producer Sylla saying: “You can’t do this! It’s not possible because this bass line is a pattern that symbolically means war in Bambara and it will be considered a provocation and I’m sure the Bambara won’t like that and they won’t buy it and will feel insulted.”

In addition to arranging instruments that wouldn’t normally be found together, Soro is also notable for how the synths of Seck, Rykiel and Bréant mimic and transpose traditional instruments. This is evident on “Cono” where Jean-Philippe’s synth mimics a diatonic balafon cycle.

“Nothing on this record is shallow” observes Bréant on the layering of sonics on Soro. “There are plenty of details. For example Brice wassy is playing plenty of ghost notes which are small strikes on the snare drum which are mostly inaudible. But if you get rid of them with a noise gate, something will be missing. It’s like cooking, there are details which make the whole thing”.

The album concludes with the devastating “Sanni Kegniba” and a soundscape that resembles the symphony of overlapping distorted speakers of many mosques that evokes a certain hour in West Africa. Over this Salif makes his final artistic statement as he invests an allegorical tale with all the gravitas and drama of his golden voice.

A huge achievement that elevated Salif to international stardom, Soro set a new bar of what could be done and sounds as fresh today as it did upon release. An era defining work, it could only have come out of the cosmopolitanism of Paris at this time as Bréant concludes:

“You know the word bastard is supposed to be pejorative and insulting in most languages? But in fact I would dare to call the music that I have done “bastard music!” I think bastardisation is the source of much richness. When you put all your vegetable peels in the soil it makes it much richer. There is traditional music of course and it’s nice because we need to know where things come from. It’s like a museum and it’s nice. No complaints about that. But I also think that as musicians we must change things – as long as it remains in good taste.”

Soro by Salif Keita, still available.